ON his voyage up the south coast of New South Wales in April of 1770, Captain Cook almost made a first landfall on the continent at Murramarang near Kioloa but was prevented from doing so by the swell and the wind. He proceeded north and named 'Pigeon House' and 'Cape St George', on the southern peninsula of Jervis Bay. It appears that he did consider entering the Bay but the winds were not favourable and so a lot of time would have been wasted in 'beating up.' Had the winds not been blowing from the southwest, Jervis Bay could have been his first landfall and the history of this area may well have been different. Cook observed the opening to the Bay and named the inner north head Longnose Point.

Lieutenant Bowen entered and named the Bay in the convict transport Atlantic in August of 1791. Three months later Matthew Weatherhead of the Matilda entered the Bay for minor repairs and named some of its features. He observed many natives armed with spears while in the Bay. In 1797, George Bass was tasked to investigate the reported existence of coal on the south coast and of a straight north of Van Dieman's Land. Whilst exploring the south coast by sea he visited the Bay and remarked that the country around it was generally barren.

It appears that the first European to venture inland in this locality was Lieutenant James Grant of the Lady Nelson who spent three days here in March 1801. He surveyed part of Bowen's Island before moving inland up to 8 miles. In February 1805 Lieutenant Bartholomew Kent and Surveyor James Meehan examined Jervis Bay. They explored overland from near present day Callala to the Shoalhaven River and up the river for about 18 miles. Several months later the crew of the wrecked cutter Nancy received assistance from an aboriginal as they made their way overland via the Bay back towards Sydney. Governor Macquarie was forced to take shelter in the Bay in 1811, on his way to Van Dieman's Land, and commented on the large aboriginal population some of whom bartered fish for tobacco and biscuits. He said 'they were very stout, well made and good looking men, and seemed perfectly at their ease and void of fear.' Macquarie sent Surveyor G. W. Evans to the Bay in March of the following year. He traced the shores of the Bay and then moved from near present day Huskisson along Currambene Creek and near Nowra Hill to the Shoalhaven River, sighting St Georges Basin from the ranges near Cambewarra, before returning overland to Sydney.

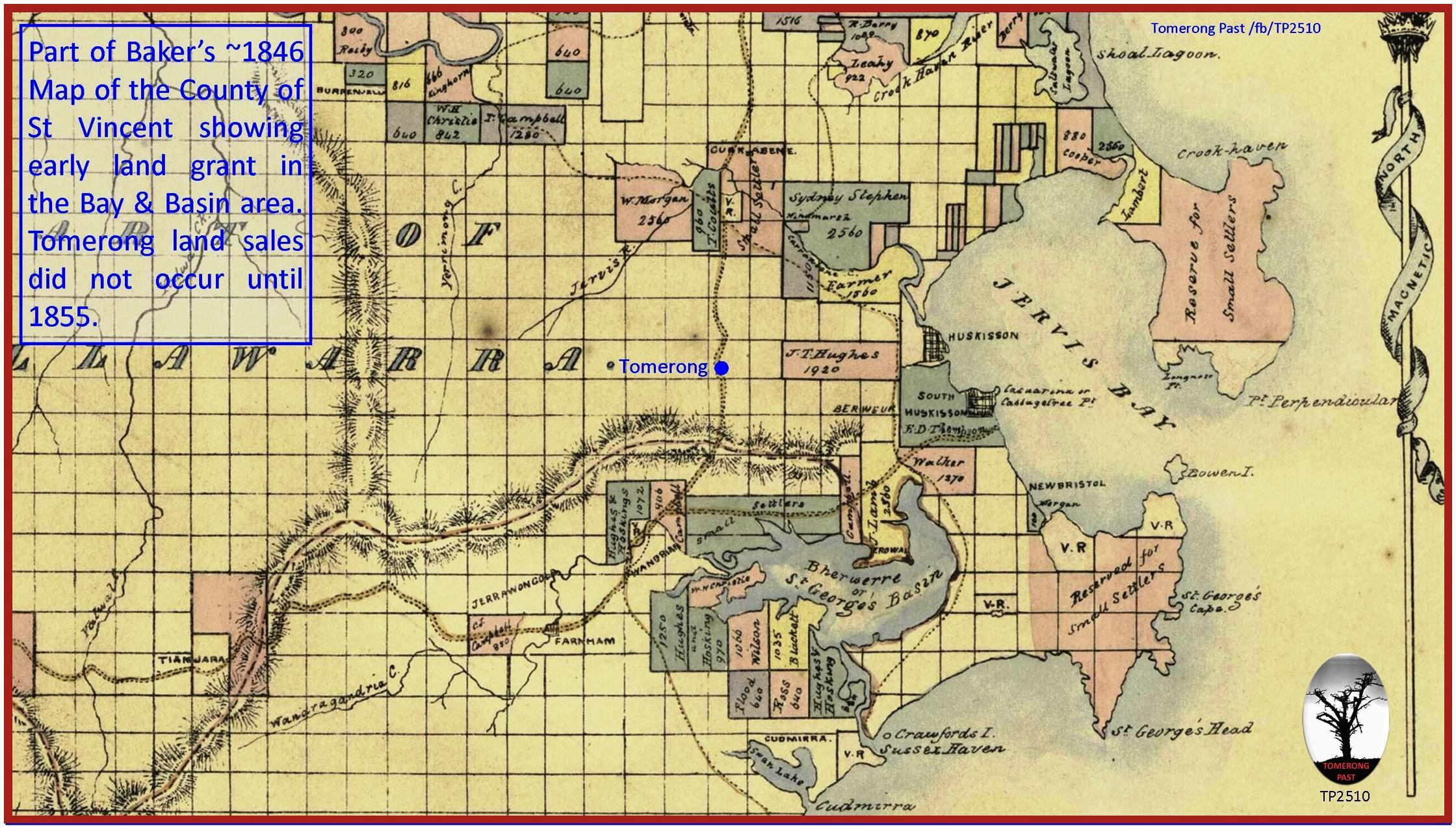

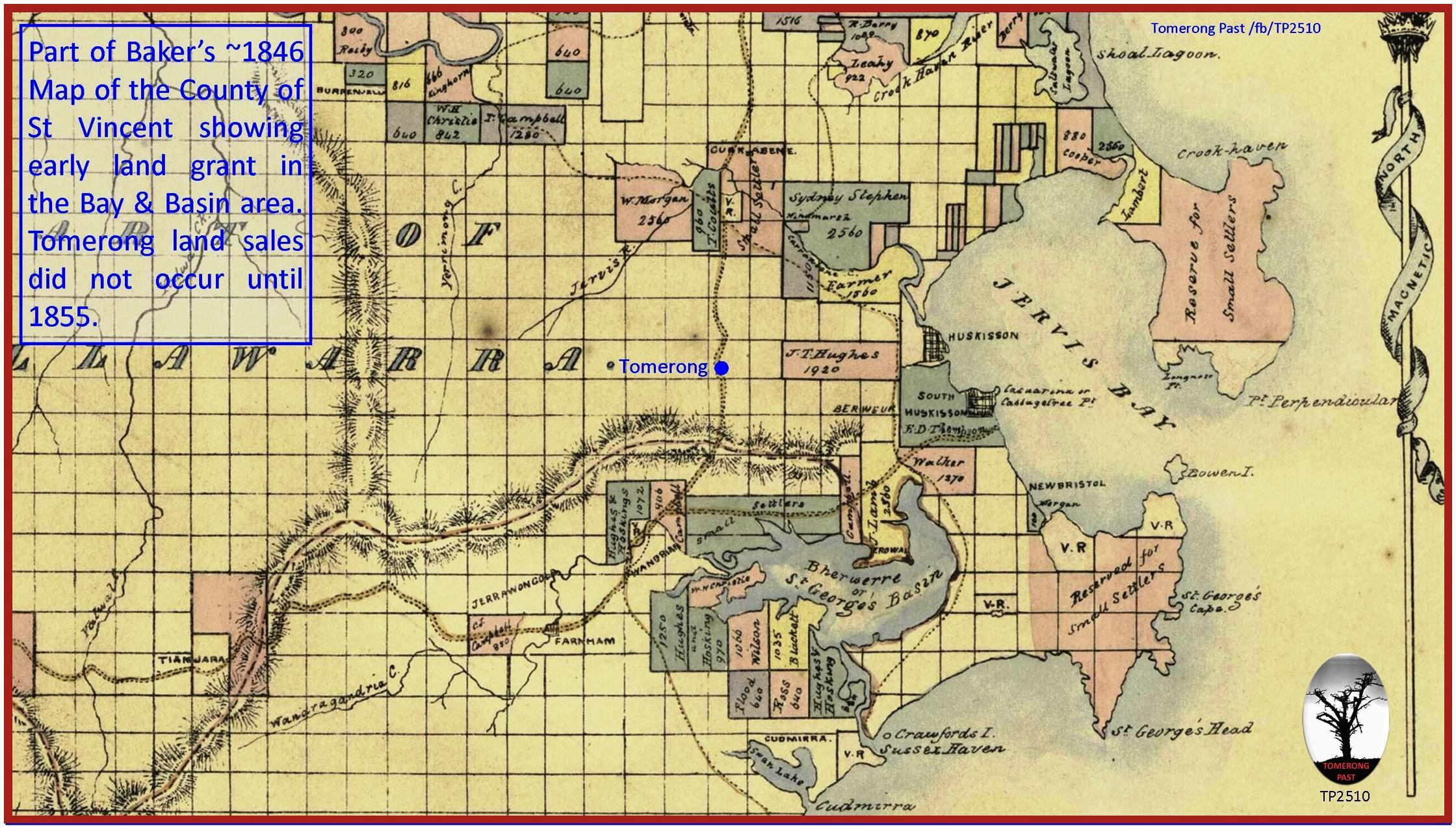

The Bay area was now being visited by cedar cutters, sealers and whalers. Cedar cutters had reputedly entered the Bay in 1813. The Surveyor General John Oxley and James Meehan examined Currambene Creek when they visited in October of 1819. Oxley was unimpressed stating 'We saw no place on which even a Cabbage might be planted with a prospect of success ...perhaps a more miserable sterile Country was never traversed by man...'. They also visited Nowra Hill. Oxley revisited in 1821 but his views did not change. Alexander Berry, however, espoused different views when he visited in February of 1822 after inspecting the Shoalhaven River. He found a considerable quantity of good land, an abundance of excellent water and good anchorage. In the following days he entered the Inlet to view St Georges Basin before moving on to Bateman's Bay and the Clyde River. In late 1827 Surveyor Thomas Florance surveyed and named St Georges Basin and some of its features including Pelican Point.

Meanwhile, others were approaching the coast overland from the west... (extract from Tomerong Local History)

The British system dictated that all land belonged to the Crown and therefore would be disposed of by sale, grant or leasing by the government. Since the commencement of European settlement in the colonies, the land rights of the indigenous population was given little consideration and to this day, is still a matter of continuing debate.

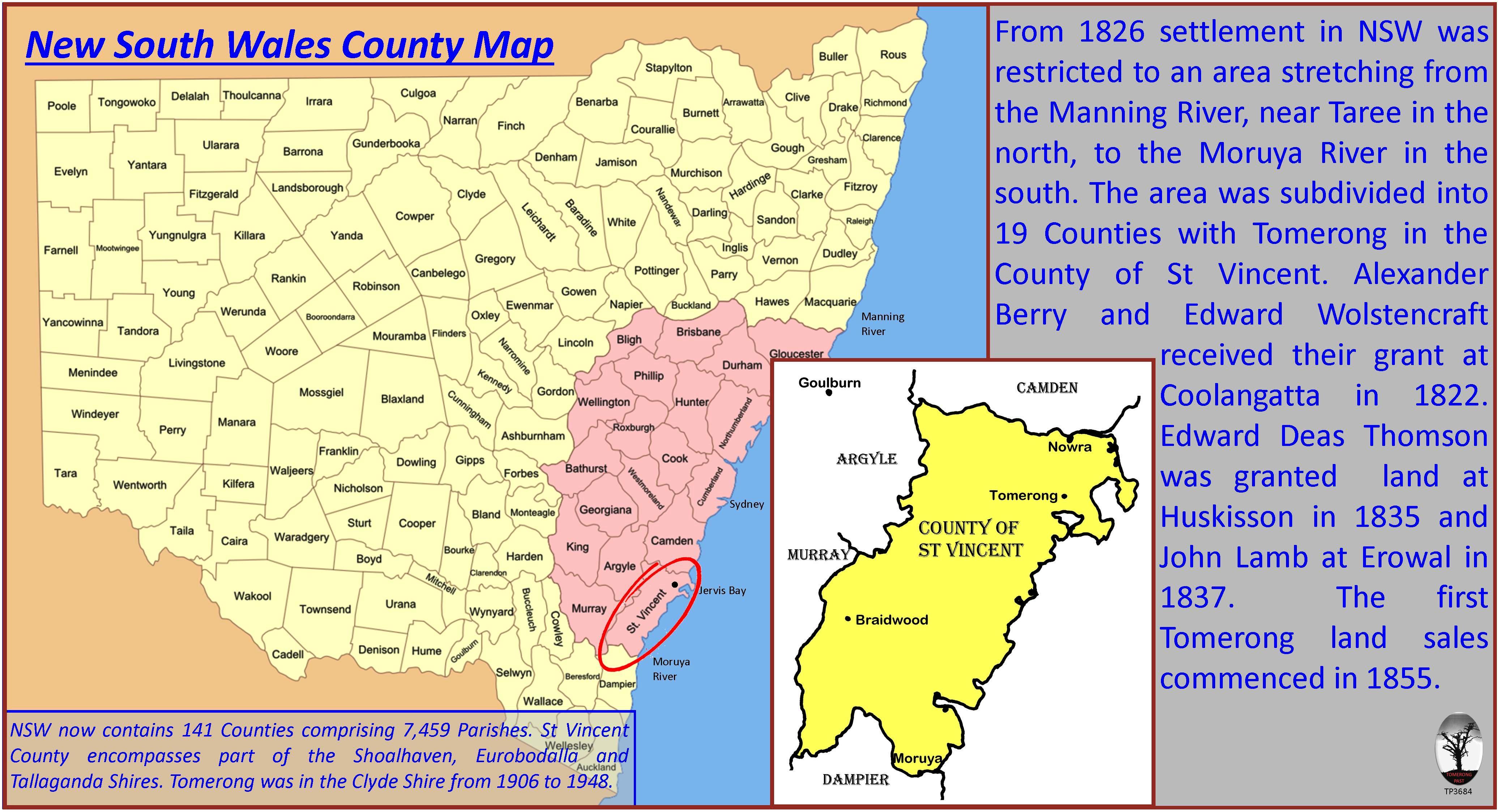

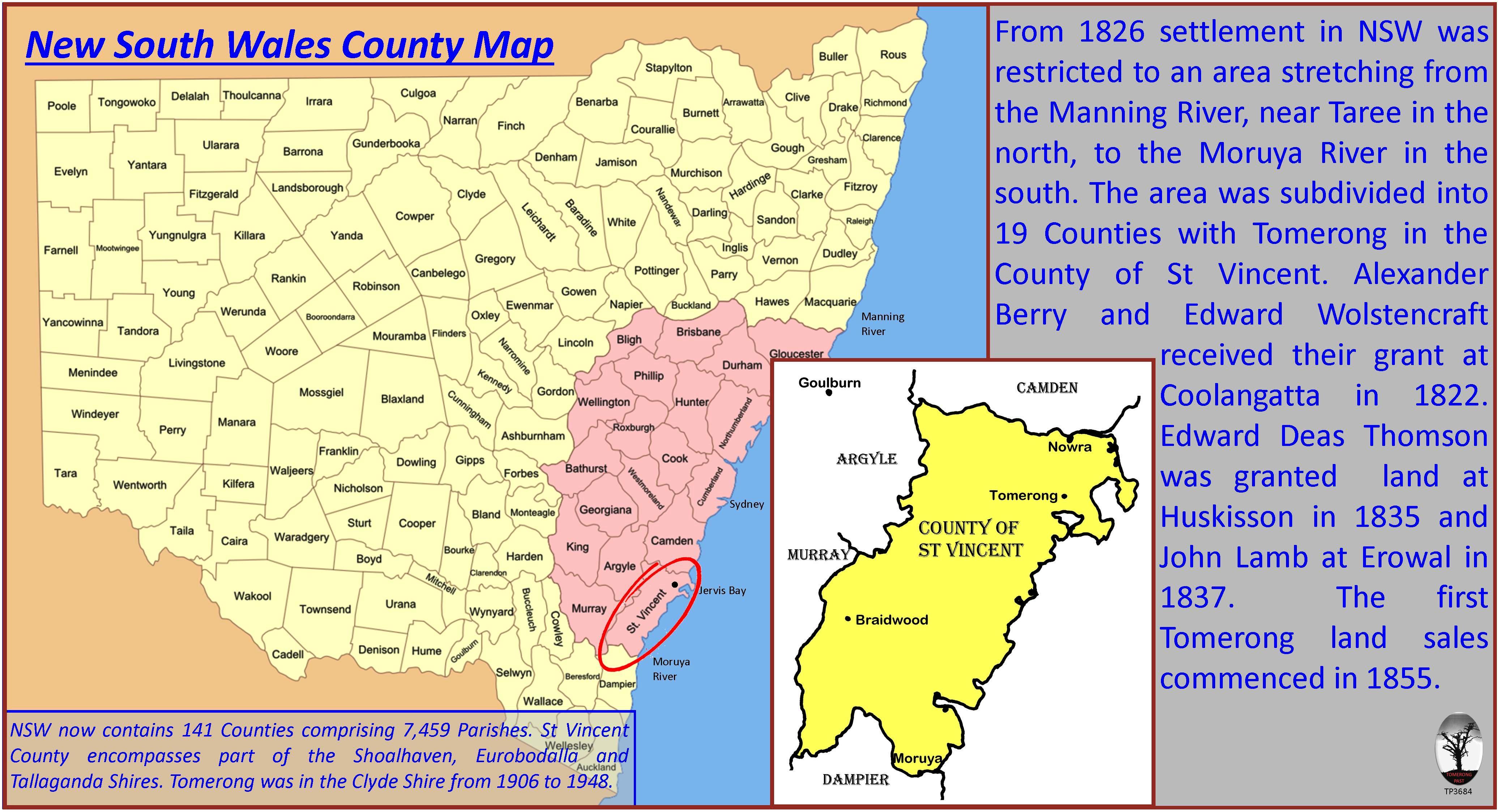

The initial distribution of land in the colony occurred when the early governors were empowered to grant blocks of land to military personnel, free settlers and former convicts. Grants could also be made under the direction of the British Government. These were known as Land Grants, or Crown Grants, and were designed to induce the receiver to remain in the colony and not return to the mother country. A system of purchasing Crown Land was introduced in 1826. Applicants of suitable character could receive a grant of one square mile (640 acres) for £500; the maximum grant was 2560 acres. Free grants were abolished in 1831.

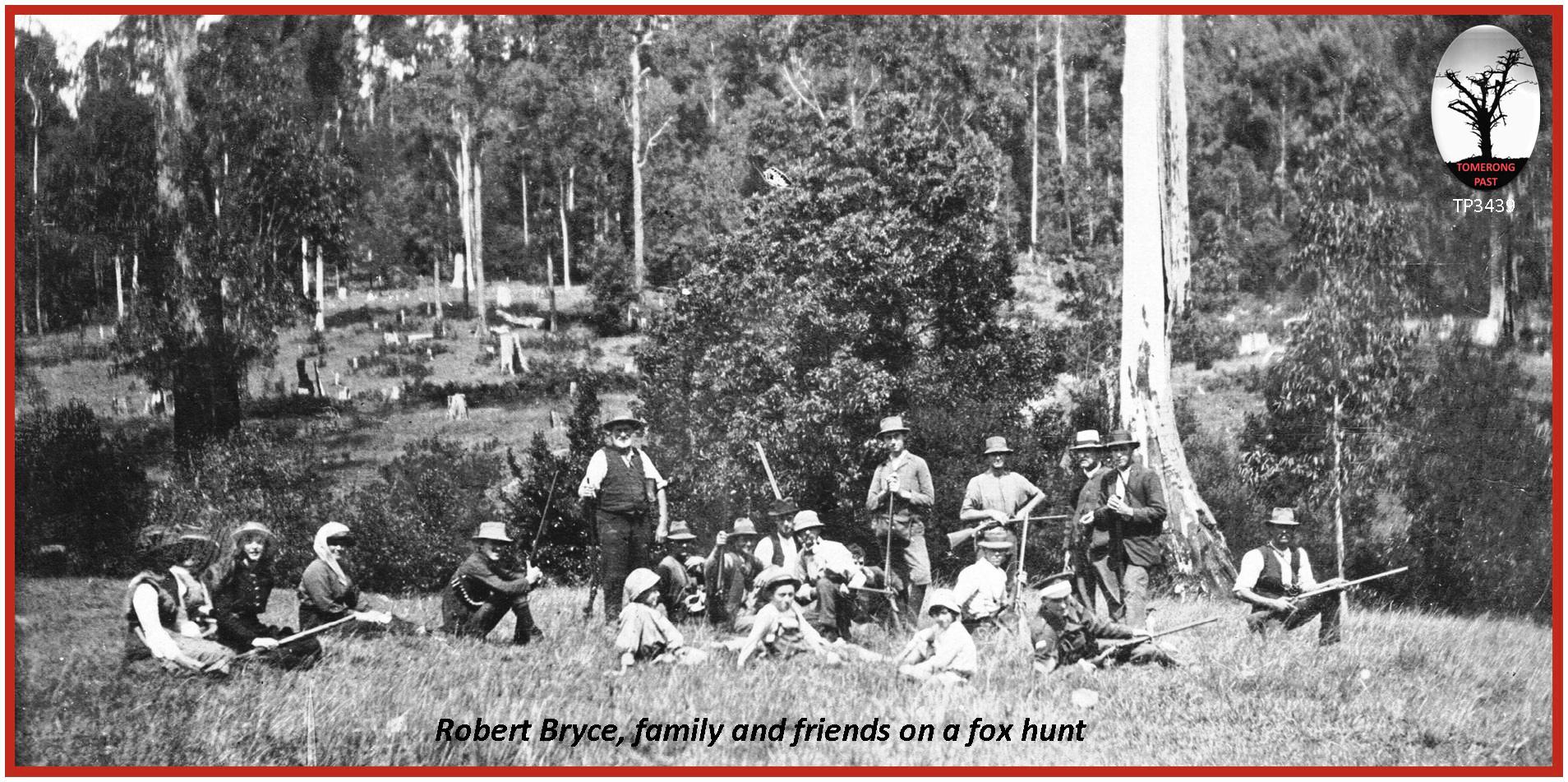

Alexander Berry and Edward Wollstonecraft had selected their grant on the Shoalhaven River in 1822. The first grant of land locally appears to have been 'Erowal Farm', which had been promised to John Lamb in 1830 and granted in 1837. In 1826 the Governor of NSW, under instructions from Britain, placed restrictions on where land could be purchased, leased or granted. Settlers were restricted to selecting land in an area of 19 counties within the Colony. The counties stretched from the Manning River in the north, to the Moruya River in the south. The County of St Vincent was the southernmost county and included the area bounded by the Shoalhaven River in the north and west, to the Moruya River in the south. In a letter to the Surveyor General dated 10 June 1831, Edward Deas Thomson selected his grant of 2560 acres on the south bank of Moona Moona Creek extending south to Lamb's northern boundary; the grant was confirmed in 1835. Alexander and William Bryce acquired Erowal in 1854 having arrived in the Colony from Scotland in the early 1850s. The brothers partitioned the property prior to 1872 (unofficially) with Alexander farming Erowal and William building a house to the west known as Cockrow Farm. Other grants would occur around the shores of St George's Basin... (extract from Tomerong Local History)

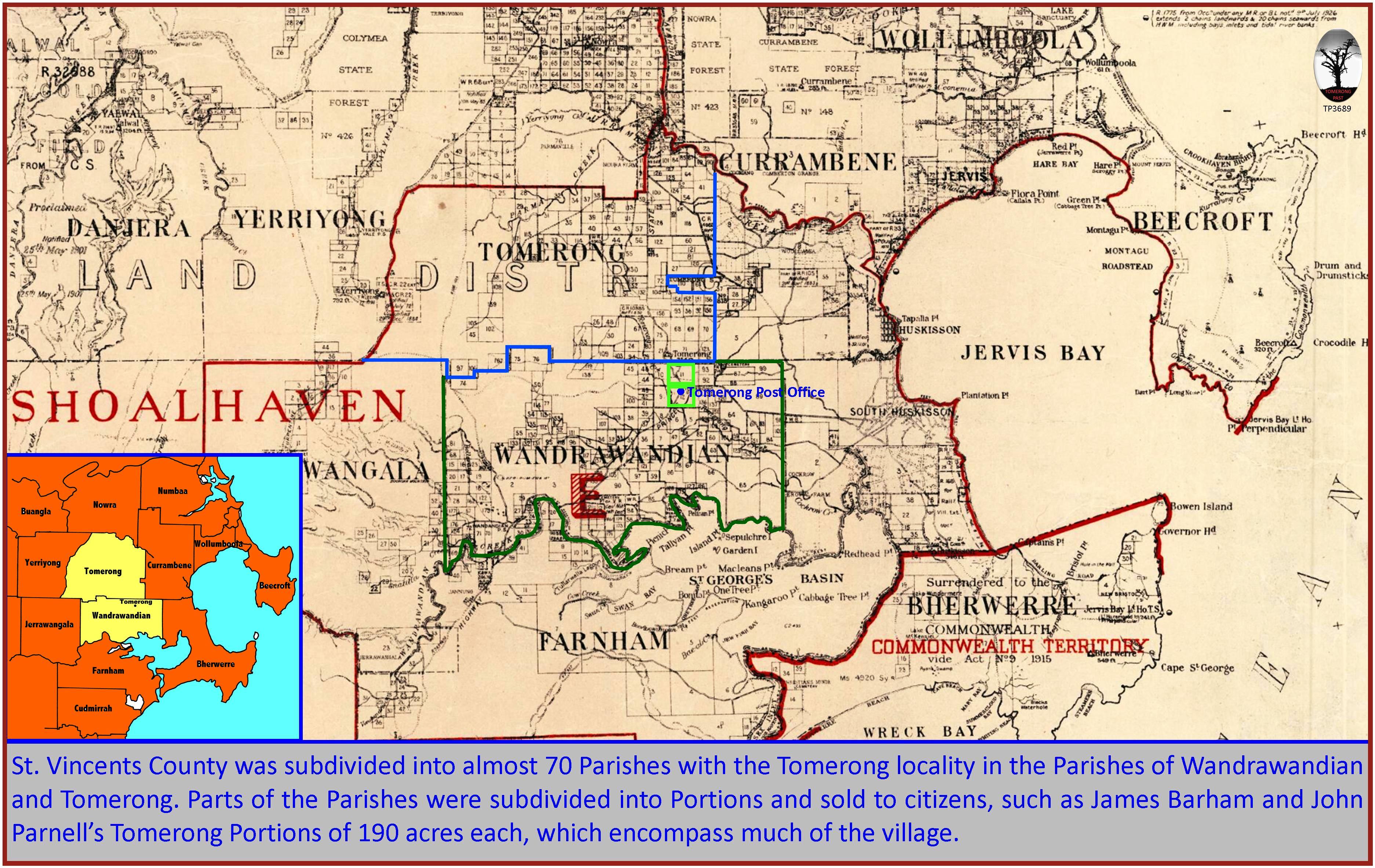

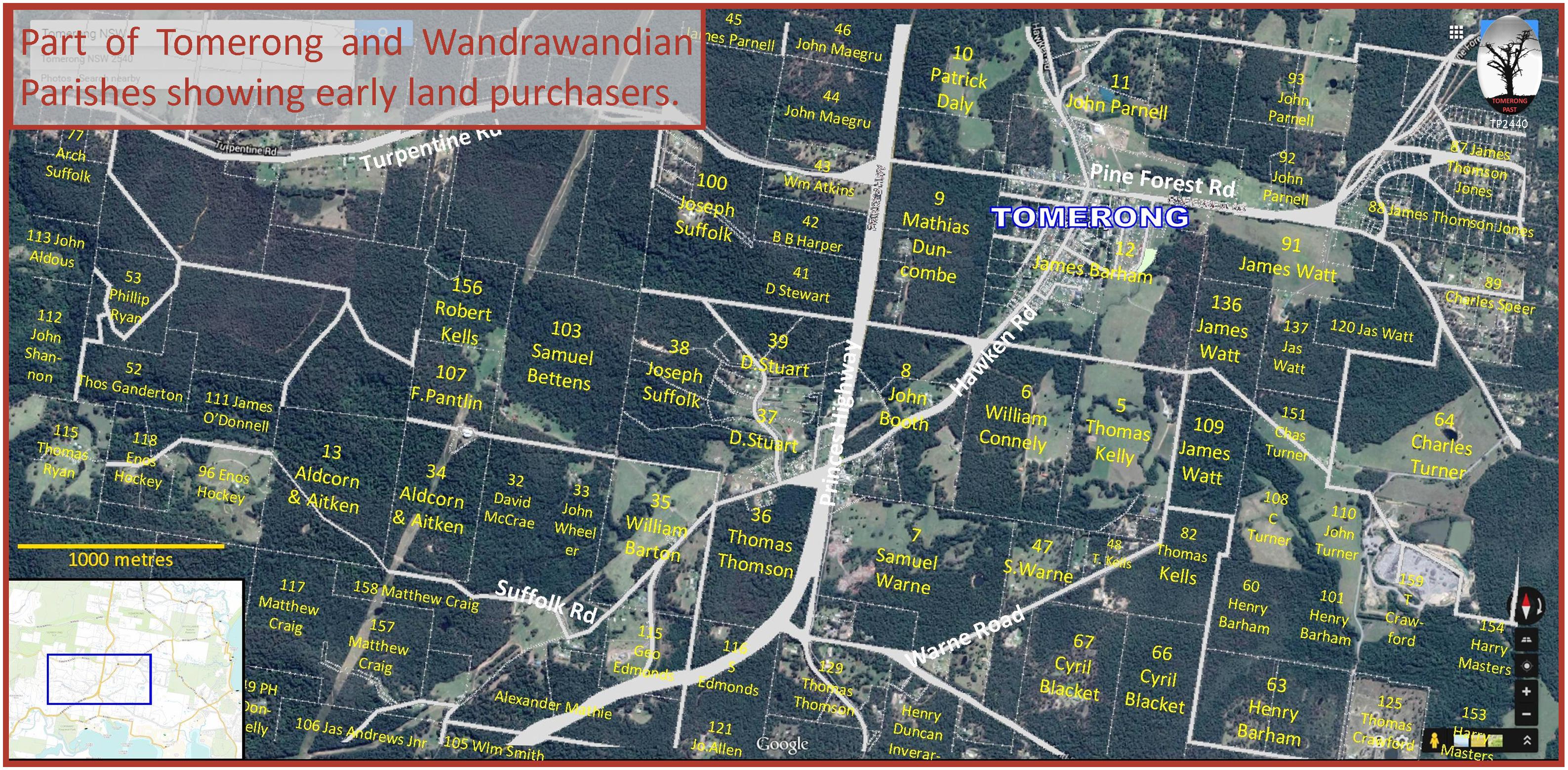

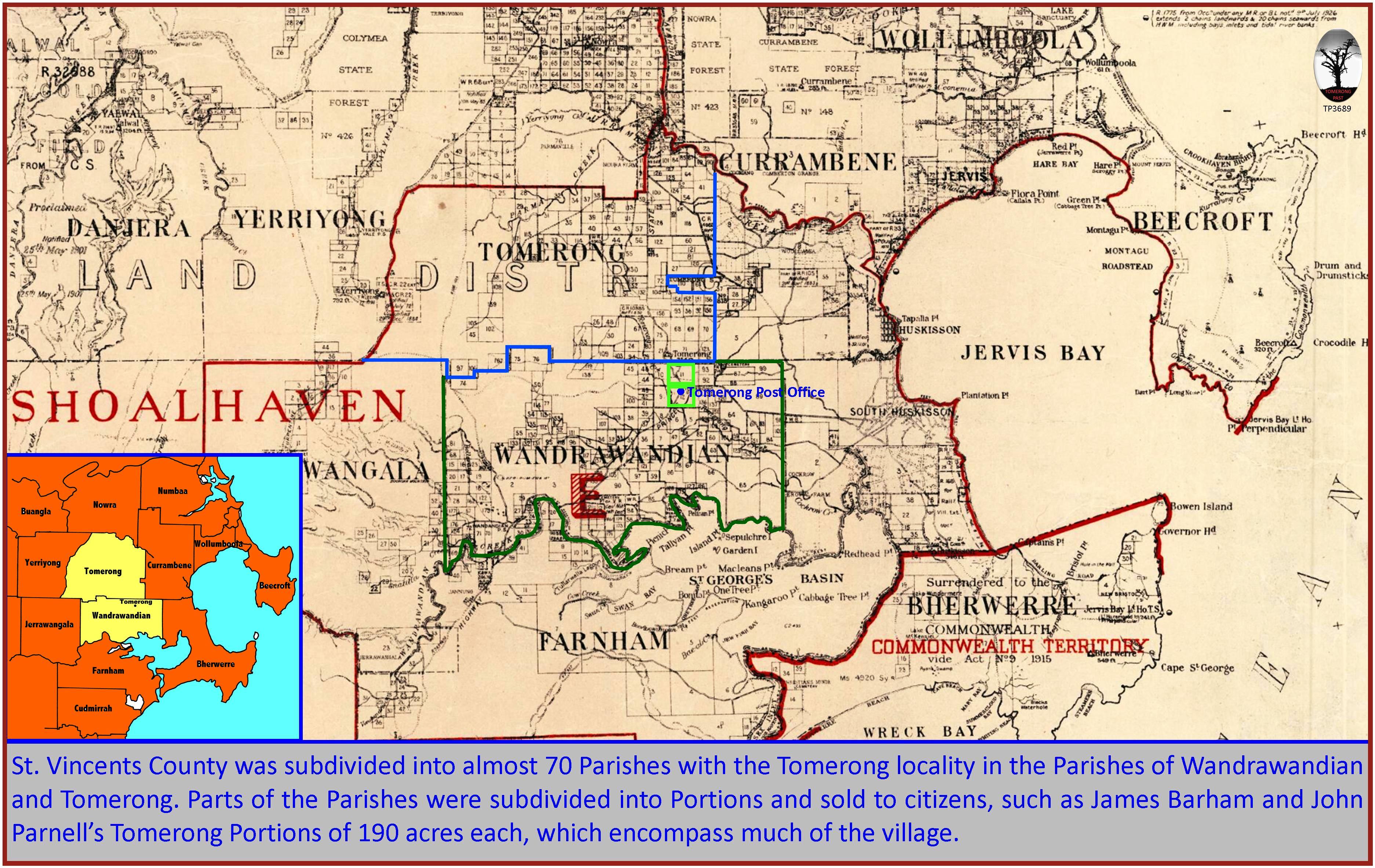

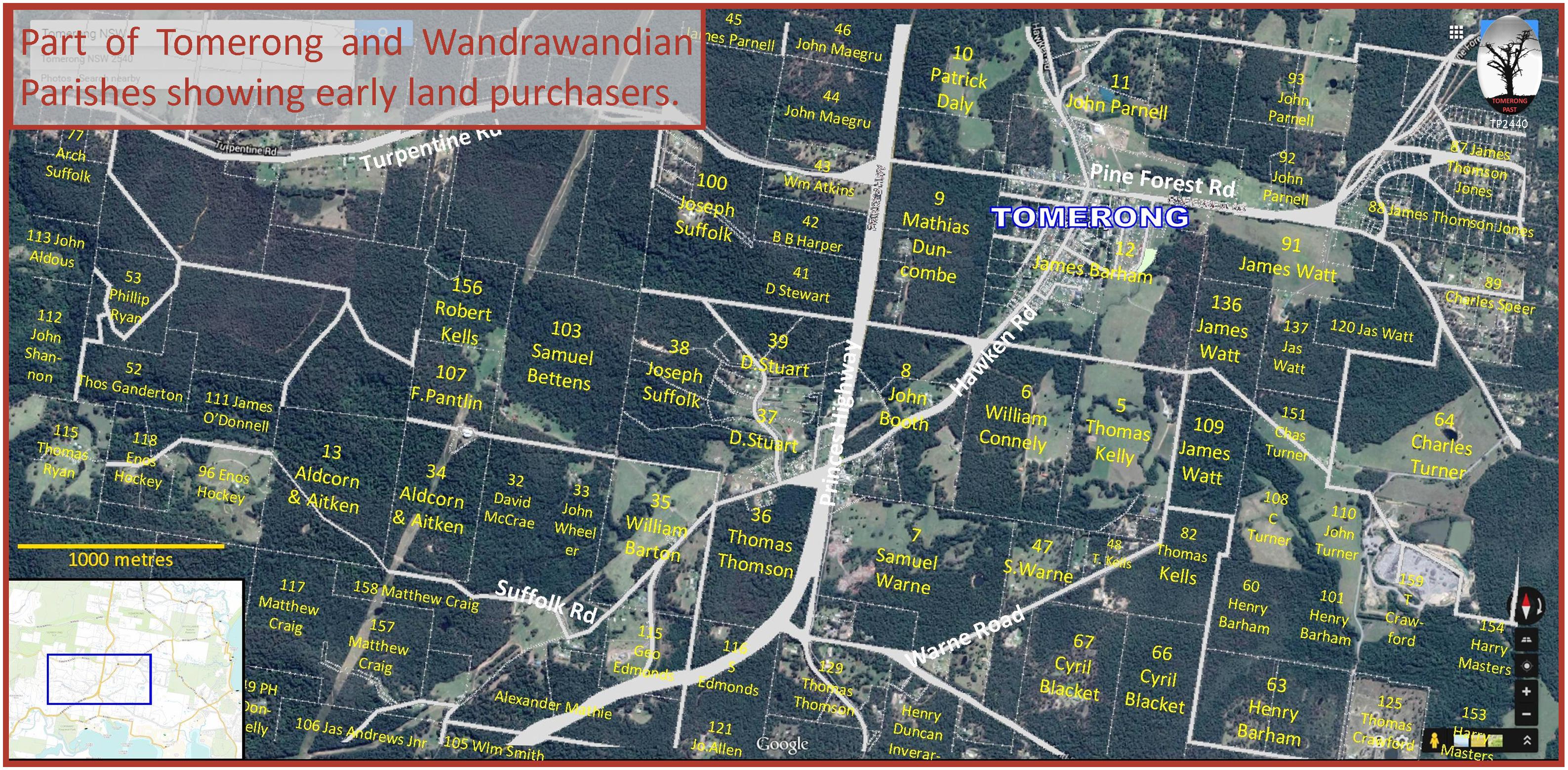

The County of St Vincent is divided into parishes. The village of Tomerong sits on the boundary of two of these parishes. The parish of Tomerong includes the area north of an east-west line drawn parallel to the Pine Forest and Turpentine Roads and crossing Hawken Road just south of Tomerong Hill. It is bounded in the north by Currambene Creek. The parish of Wandrawandian covers the area south of the Tomerong parish to the shores of St Georges Basin.

The surveyed crown land within the 19 counties in 1831 was to be sold at auction for a minimum price of 5s an acre, or leased at a minimum of £1 for 640 acres (one square mile). It would be sold in lots of 640 acres after being advertised for 3 months. Military personnel were given discounts or grants proportional to their rank and length of service. Part of the profits from the land sales was used to sponsor an immigration scheme to provide labour for the colony. In 1839 the cost per acre was raised from 5 to 12s… (extract from Tomerong Local History)

Most of these early land grants/purchases were for larger areas of land that were suitable for grazing and had access to Jervis Bay, Currambene Creek or St Georges Basin. The next most attractive land was that which bordered other water supplies such as Tomerong Creek. Tomerong was not a government gazetted or a private township. It evolved to become a village because of its position and the settlement that occurred. The first division of land at Tomerong was surveyed in a rectangular block that included the creek and the Shoalhaven to Ulladulla Road. It was proclaimed on 7 April 1855 and the sale took place on 8 May at the Nowra Courthouse… (extract from Tomerong Local History)

A second sale of surveyed land, which adjoined the lots from the first sale, was proclaimed on 17 July 1855 and occurred on 22 August 1855. The interest in this sale was not as strong as the first as it appears not all lots were bid for, and some were purchased at a later date. Also, more of these lots were sold at the minimum price... (extract from Tomerong Local History)

For the new selectors of land at Tomerong their principal concern would have been to clear the land of its native forest to enable the planting of crops, the grazing of livestock and the establishment of a dwelling. The Conditional Purchase laws of 1861 also demanded improvements to the property and this could be achieved by clearing the eucalypts and establishing fenced paddocks. Ringbarking would undoubtedly have been used to kill the trees. This was achieved by using an axe to cut a ring around the trunk about a metre above the ground. The cut was deep enough to prevent the flow of food from the roots to the leaves. Poison would also be used below the cut, as the eucalypts would sprout back if left unattended. Ringbarking was sometimes favoured over tree felling as it didn't clutter the ground and therefore allowed grass to grow and stock to graze beneath the trees. Trees could be felled by axe, or they could be cleared by grubbing around the base of the tree, cutting the lateral roots and using a pulley and winch to pull the tree down. Photographs of the village taken about 1908 show far fewer trees than we are used to today and many of the larger trees were dead from ringbarking.

To provide a habitable building for the family, basic lodgings could be constructed using an earthen floor and bark roof. The wide strips of bark could be flattened with a weight or by heating over a fire. Walls could be made of vertical slabs of timber split from a log using wedges and an axe or adze. The construction could be held together with vines tied to supporting poles. Better walls could be constructed if the logs were pit sawn along their length. This method produced a more even thickness, wider slabs and a smoother finish so gaps were not so large. An improved roof could be made of split shingles or, as it became available, corrugated iron.

Subsistence farming was a necessity for the early settlers of Tomerong. The families grew their own vegetables, produced their own butter and cheese and raised their own livestock. Excess produce and fattened livestock could be sold to provide an income for further farm development. Large scale crop production was very much a gamble for the early settlers as even the most competent farmers were at the mercy of unpredictable weather conditions, so dissimilar to those they were used to. Unfortunately most of the land was not suited to large scale crop production and many small selectors would struggle to make a living. For some, the timber would be their saviour, either as a resource or as a line of employment... (extract from Tomerong Local History)

Back to Top See the More Information page for additional information. The Next Page covers Families.